Joint replacements are one the most common surgeries, crucial to enhance mobility and relieve pain for some individuals. Demand for these procedures is increasing, and various programmes within the NHS – such as the Getting it Right First Time programme (GIRFT) – have considered how to improve care by reducing ‘unwarranted variations’ through best practice guidance and support for patient pathways. But where are the voices of patients and the public, in schemes to improve patient pathways?

In this blog, Dr Sarah Jasim reflects on a recent exploration which delved into the perceptions of patients and the public regarding planned improvements to the NHS joint replacement pathways. She explains how respondents at focus groups visualised the pathway, saw the biggest blockers, and how their voices could and should be involved across the full patient journey – from initial symptoms to post-operative care.

With our increasingly ageing global population and a growing trend for joint replacements earlier in life, these are now one the most frequently performed and effective surgical procedures around the world. Given the significance of their impact on health and care services, the NHS has a care pathway to support planning the care of patients who undergo this type of surgery. Care Pathways – from first consultation to discharge from after-care - draw on research evidence and best practice to give a framework for how different components of care should be optimised and sequenced, to enhance quality and improve patient safety. (For more information on Care Pathways, our partners at East London NHS Foundation Trust have a good explanation here.)

Programmes such as GIRFT recognise the importance of clinical perspectives as central to pathway development, but we believe there are important learnings to be heard from current and future patients who must navigate this pathway too – particularly as previous studies on patient involvement in quality improvement have shown that there is often a ‘tug of war’ over whose knowledge takes precedence.

What did we do?

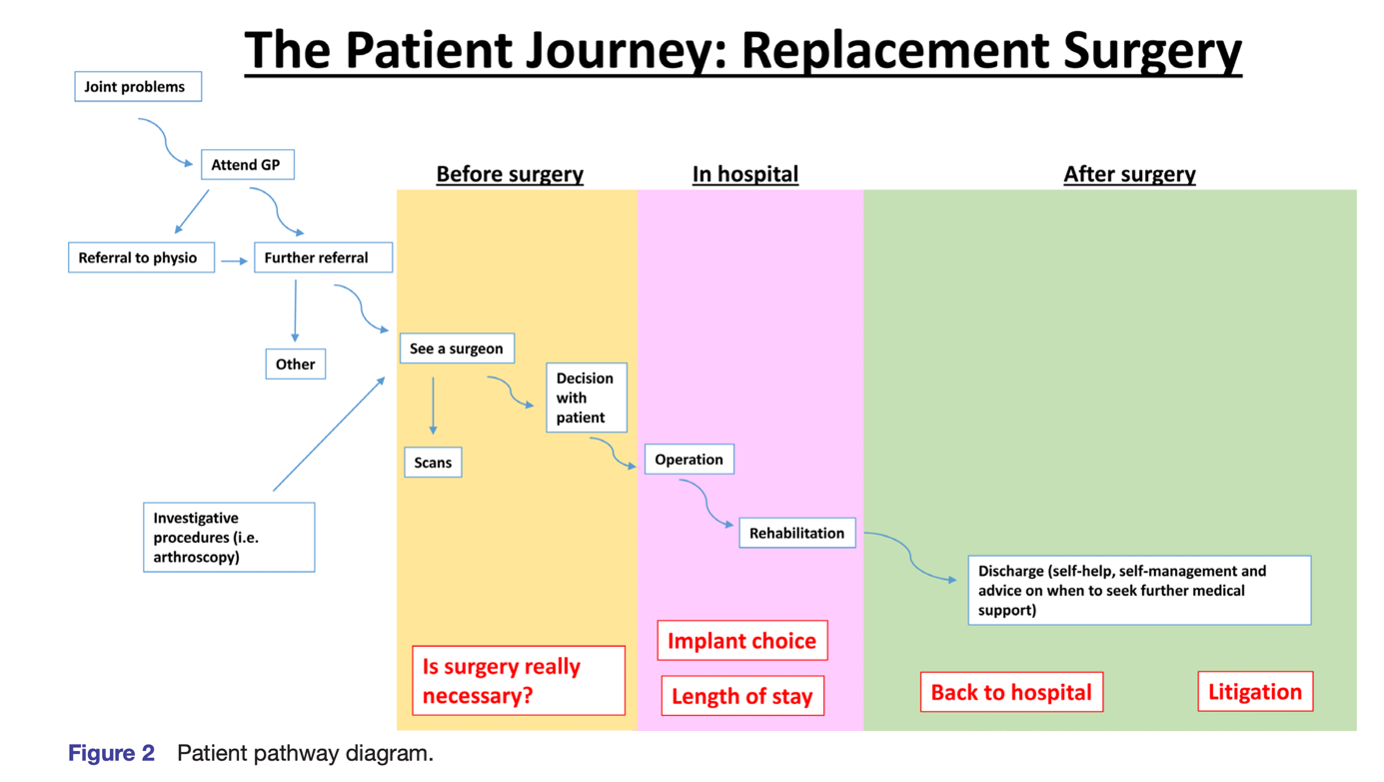

We spoke to 14 individuals in qualitative focus groups, gathering insights from patients who had undergone TJA in the last two years, as well as individuals aged 60 and above who had not yet undergone the procedure, but were in the age group most likely to. Each focus group was co-facilitated by a research partner and patient advisor, Mr Raj Mehta – who advised us to use a simple diagram of the UK TJA care pathway. However, Raj called this a patient journey instead, based on clinical guidance at the time.

The findings revealed significant concerns that patients and the public faced throughout the entire patient journey.

1. The ‘maze’

Although time in hospital is often the focus of improvement efforts, our focus group attendees argued that the patient journey begins before individuals present to primary care. ‘…… that’s [pointing to the first part of the patient journey diagram] probably where most problems, as far as I’m concerned, arose. In that trying to see a consultant was very difficult.’

‘…if you like, you’d need a referral to Social Services. I think that should be part of the pre-operative planning rather than suddenly realising afterwards-’

Contrary to the streamlined, linear process presented in clinical guidelines, patients described their journey as a complex ‘maze’. This perception was amplified by a lack of timely information and imbalances of knowledge and power between patients/public and care providers. They expressed feeling 'left in the dark' with insufficient information about the process. This deficit hindered their ability to make informed choices. Some were unaware that they had choices in selecting the hospital or surgeon.

‘I was just taken aback by how much I felt like a widget on a production line.’

They had concerns about other aspects of the pathway, such as obtaining a surgical referral, with pre-referral interventions aimed at potentially avoiding the need for surgery (i.e. physiotherapy) being perceived as a mechanism to restrict access to hospital care.

2. Power dynamics and obstacles

Our group highlighted power imbalances in their interactions with health and care professionals. Negative encounters could significantly affect their experience and progress along the pathway.

‘I was so intimidated by him, and so overwhelmed by him, I thought, ‘Right, okay, well, you know, I’m just going to … there’s no point in my doing anything else here’.’

Participants described three distinct sources of knowledge which they drew on to differing degrees to overcome the obstacles they faced: formal learning (such as ‘Joint Schools’), informal learning (such as undertaking their own research before attending appointments) and lived experience (as some patients had previously undergone multiple joint replacement surgeries).

What next?

This study underlines some areas for improvement – but primarily, the need for a better involvement approach to improving the joint replacement pathway. The linear conceptualisation of the TJA pathway, which is often how researchers, practitioners and policymakers view the pathway, stands at odds with patient experience.

Improvement programmes focussed on hospital care can fail to consider patient concerns and priorities about the rest of the pathway, and public and patients’ entire experiences. We advocate for patients, users, and carers to be directly involved in improvement programmes, to ensure that patient experience is optimised, as well as informing related processes and important outcomes of care.

30 Sep 2023

30 Sep 2023